Wanderlusting the Juana Lopez Member

Ninety million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period, the Farallon Plate was subducting under the western coast of North America. This threw up the great volcanic edifices of the Sierra Nevada, whose weight flexed the North American Plate downwards. This created a great waterway, the Western Interior Seaway, that stretched from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. The Jemez area was drowned in this seaway, and the thick marine shale beds of the Mancos Formation were deposited throughout the area.

The Mancos Shale is one of the largest formations of the western United States, both in its thickness (as much as three miles in some locations close to the ancient Sevier mountain front in Utah) and lateral extent. Mancos Shale is mapped from central Utah to our area to central Colorado. The Tropic Shale of southern Utah and northern Arizona, the Pierre Shale west of the Rocky Mountains, and the Cody Shale of Wyoming may be part of the same great sea bed.

So thick a formation begs to be further subdivided into members wherever distinctive beds can be found within the formation. One of the most widely recognized of these is the Juana Lopez Member, first described in 1944 in a railroad cut southwest of Santa Fe. The member was named for the nearby Juana Lopez land grant and it is distinctive for forming a horizon of shaly limestone and limy sandstone, with a characteristic yellow-brown color that contrasts with the deeper brown color of the rest of the Mancos Shale. The Juana Lopez Member is somewhat more resistant to erosion that the rest of the Mancos Shale, so it tends to cap low mesas, cuestas, or hogbacks. It also tends to be rich in fossil molluscs of the Cretaceous, though not all outcrops are as rich as others. One of the best-known sites is the Windmill Site in the San Juan Basin, not far from Cabezon Peak. I have also found good specimens at a similar low ridge north of the Windmill Site.

As sometimes happens, geologists became dissatisfied with the original type section of the Juana Lopez Member. For one thing, it turns out the section reported as its location in the original paper does not actually contain any Juana Lopez Member. The next section over has the rail cut with the good exposure. This was likely a misprint in the paper, but it puts an asterisk after the original definition. For another thing, the type section is not that great; it does not contain the complete thickness of the member as it is most naturally defined.

Unpacking that: Land in the United States is typically surveyed using a somewhat arcane system based on a central meridian and line of latitude in each state. In Utah, these lines cross at the southeast corner of Temple Square in Salt Lake City. In New Mexico, the lines cross in the middle of a farmer’s field in San Acacia, north of Socorro. Go figure. Anyway, geological locations, particularly in older writings, will specify a location something like T15NR10ES31 which is read as “Township 15 north, range 120 east, section 31”. You can find maps for at least some states online that show the public land survey sections, and most geological maps show them as well.

The original definition of the Juana Lopez Member was of a single 30′ interval of shaly limestone. Later it was realized that this was just the topmost and most prominent of a sequence of intervals of shaly limestone separated by shale. The entire sequence is now included in the Juana Lopez Member. Problem: This made the original type section unsatisfactory, but a rock unit is forever tied to its original type section, the way a species of organism is forever tied to the original type specimen. The fix is to designate one or more reference sections to supplement the type section, and this was done for the Juana Lopez.

Long intro, I know. Bear with me.

The type section of the Juana Lopez is unsatisfactory for a third reason, at least for me: It’s inaccessible. The railroad cut belongs to the Santa Fe Railroad, it’s fenced off, and the only legal way to get in and take a picture of it (short of being a professional geologist who gets special written permission) is to ride the train and snap a photo as the train passes the cut. This seems impractical.

The reference section, on the other hand, is on public land, with a dirt road from the paved highway that goes right up to its base. This assumes you have a vehicle up to braving the dirt road. I don’t, but my friend Gary Stradling does. And the paper describing the reference section is full of fossil mentions, so it seemed possible there might be good fossil hunting there. Gary was all in, and we headed out Saturday morning to check the site out.

Our route took us through the Jemez Mountains and San Ysidro onto the highway north towards Cuba. About eleven miles south of Cuba, the old Highway 11 branches off to the east. Just after the pavement ends, there is a dirt road to the east with an (unlocked) gate. This isn’t a great road, but the only really bad part for a good 4WD high-clearance vehicle is the arroyo crossing. You do not want to attempt this in a passenger vehicle; trust me. But Gary scouted the crossing, pronounced it doable, and then proved that it was doable for Obsidian, his jeep. From there it’s less than three miles on (somewhat rutted) dirt road to the reference section. We turned the jeep around, parked, and headed out, with one eye on the weather. (We did not want to get caught here by heavy rain. Wet Mancos Formation turns to glue.)

Above us was the Juana Lopez, capping a hogback ridge.

For new readers (Welcome!): Almost every image at this site can be clicked to get a higher-resolution version. Almost all blue links take you to the location on Google Maps where the associated photograph was taken.

Notice that the top of the ridge has a more pronounced yellowish color. This is typical of the Juana Lopez.

We head up the ridge, and find some poor fossils almost at once.

These aren’t keepers, but they suggest that better stuff can be found with some hunting. We proceed up the ridge

and onto its crest.

This panorama looks to the west, where we see La Ventana Mesa West on the far skyline. The sandstone layers of the Point Lookout Sandstone cap this mesa, and also cap some nearer mesas at left. We passed some on our way in.

The ridge is a hogback, with the rock layers dipping to the west at about a 45 degree angle.

The calcareous sandstone bed here seems a likely candidate, but we see no obvious fossils. We continue hunting along the ridge. More steeply dipping beds are visible to the northwest.

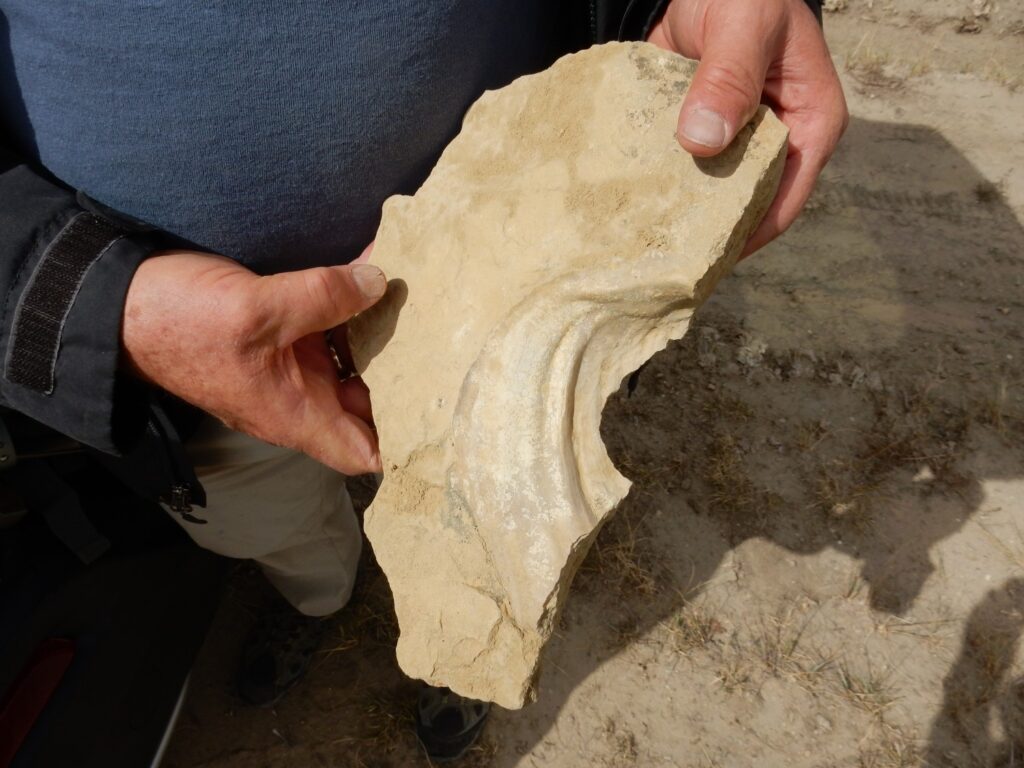

Slab with sedimentary structures.

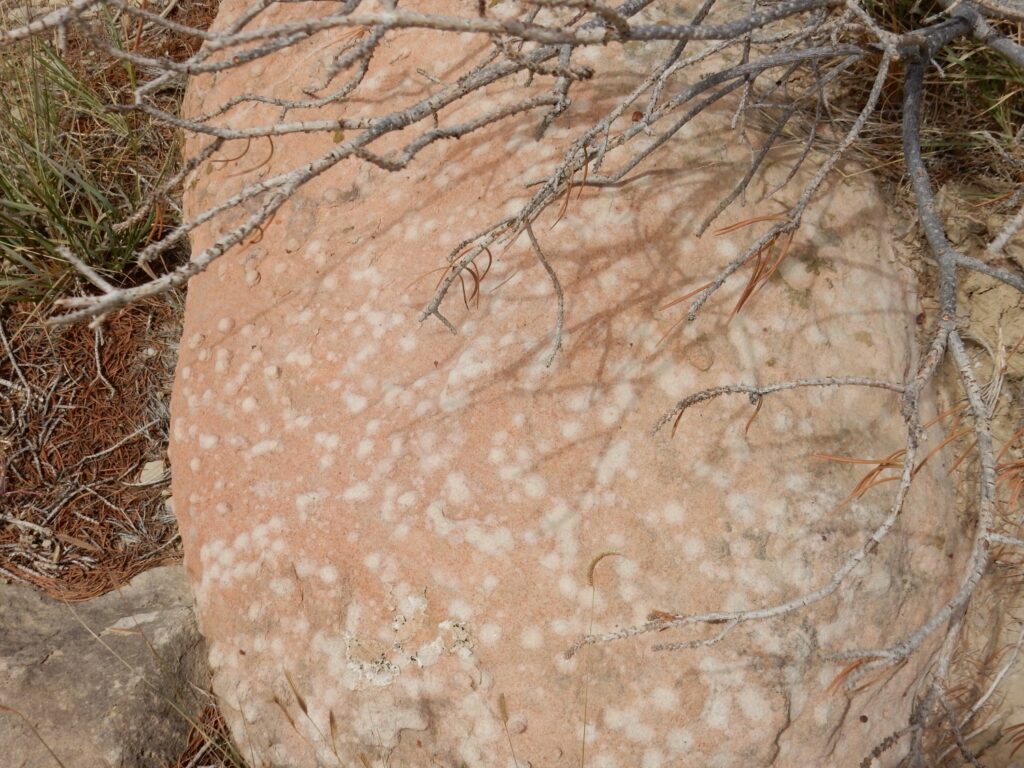

We’re not having much luck here. My guess is that the crest is the uppermost bed of the Juana Lopez, and everything to the west is much less fossiliferous shale of the Niobrara Member. We descend (carefully) back down the steep eastern side. There are some interesting rocks here

showing an interesting concretionary structure. Also here:

This is a fairly clean sandstone, possibly erosional remnants of overlying Point Lookout Sandstone — clean sandstone is rare in the Mancos Formation in our area. Gary wonders if the first might be a coral, but that’s more a limestone thing. Sandstone does preserve trace fossils well, and I could almost imagine that this second rock is showing some form of trace fossil, but I think inorganic concretions or nodules is a better guess.

Trace fossils: These are things like burrows and footprints left by living organisms that are not actually the living organism itself. Nodules versus concretions: Concretions form around a nucleus sometimes, often a fossil, while nodules have no obvious nucleus.

These could be fossil borings.

Come to think of it, that first rock might in fact be a kind of trace fossil called Entobia that is known from rocks this age of the Western Interior Seaway. Via Wikimedia Commons:

I do see a resemblance.

About this point we run across a fairly spectacular fossil oyster.

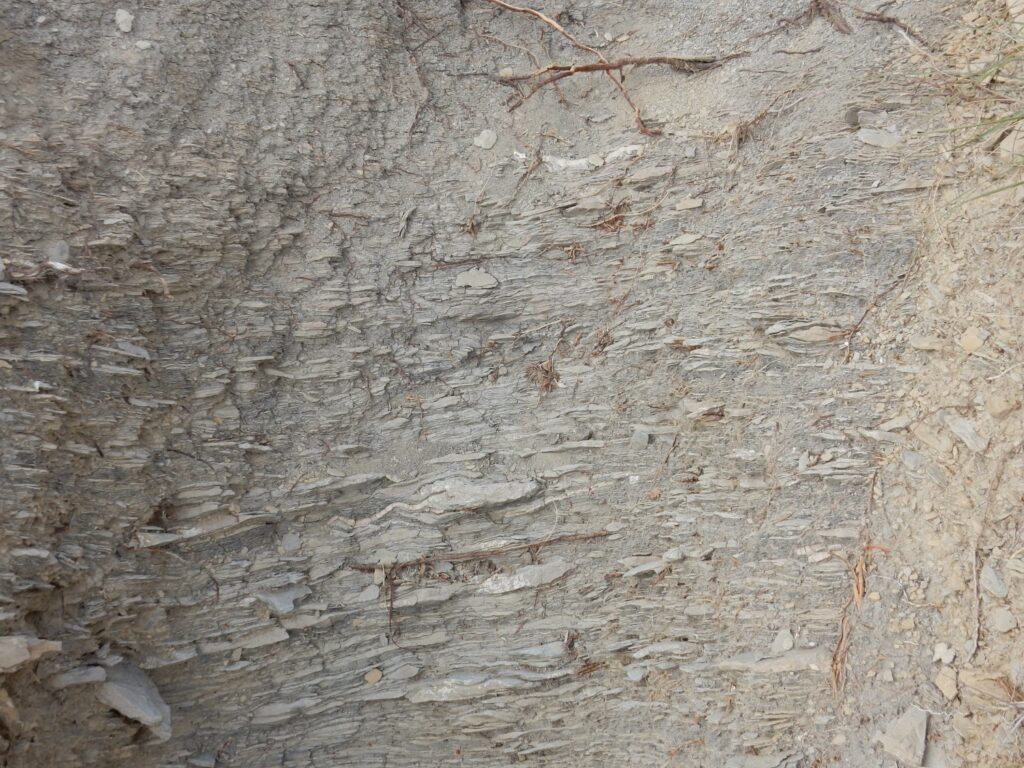

Thus encouraged, we begin working up some steep gulleys back towards the top of the ridge. The shale turns out to be almost ideal for climbing, with just enough give for solid footing. Shale:

However, this may not be ideal rock for preserving fossils.

There is a bed of gypsum just below the crest.

Gypsum is an evaporite, formed in brine where pooled seawater evaporates. It suggests that late in Juana Lopez time, the Western Interior Seaway retreated almost completely from this area, leaving salt flats and brine pools in which gypsum was deposited.

Another look down the crest of the hill.

We haven’t had a lot of luck. But this was a first exploratory visit. We may come back again. Meanwhile, Gary suggests visiting the Windmill Site one more time. I’m game.

First, a panorama of the Dakota hogback to our east.

The near hills are lower Mancos Formation shale, but the harder sandstone forming the ridge beyond is Dakota Formation and Morrison Formation. The Dakota Formation is early Cretaceous sandstone deposited during the initial advance of the Western Interior Seaway into this area; this forms the flat western of the ridge:

The more colorful beds towards the top of the ridge are Morrison Formation, of Jurassic age. These were deposited in a river system that preceded the Western Interior Seaway, and they’re famous for their dinosaur fossils. (But only in select locations; I know of none here.) The entire ridge, like the Juana Lopez hogback, is tilted at about 45 degrees. This whole area was folded upwards around 40 million years ago, when the great crustal block of the Sierra Nacimiento was thrust upwards during the Laramide Orogeny. We’re standing on the western side of that thrust block.

One last photo of the Juana Lopez at its reference section; I think this will be the one for Wikipedia.

Gary returns to the car with a couple of fairly spectacular fossils.

I didn’t entirely strike out myself.

All are relatives of Inoceramus, an oyster cousin from the Cretaceous. Some species grew six feet across. No, we didn’t find the really huge ones — but these are not bad.

Verdict: While we found few fossils on this first trip, what we found was very promising. This area may be worth visiting again. If I’m reading the lay of the beds right, the best places to look are probably on the east side of the hogback.

We return to the paved highway, once again daring the arroyo crossing. (Really, we have no choice at this point.) This is reasonably uneventful and Gary is proud of Obsidian. From here we proceed to the Windmill Site.

A word of caution: We came in via Highway 279 and the pipeline road. Where the pipeline road crosses Arroyo Chavez, there is presently a spectacular pool of mud in the middle of the road. Gary took it with Obsidian set to sand/mud terrain; only a lunatic would try it in a regular passenger vehicle. There are other ways to get to the site and they are probably preferable until some work is done on the Arroyo Chavez crossing. (Which really ought to mean installing a proper culvert.)

We are parked next to a major power line from Four Corners to the Albuquerque area. The insulators holding the lines are impressively long, and you can actually hear the crackling of the power lines from where we are parked.

We spend a fair amount of time scouting the area. I find numerous oyster fossil fragments, but not many real keepers, and no ammonites today. Still:

A few nice shells, and the prominent burrow trace fossils.

Slab of mollusc shells.

We are not the only ones there. A family with young children are collecting crystals from the numerous shattered concretions in the area. They are the Colette family, and it turns out that they are friends of the Wanderlust; they got the location of the Windmill Site from one of my earlier postings. It’s always nice to meet readers.

Gary and I head out. But not without a stop for some impressive river terraces along an unnamed arroyo.

There’s something very weird about this arroyo, if you examine it in Google Maps. The upstream branches end abruptly at deep lips; not so strange in itself, as I believe this is typical rapid headwards erosion of gulleys following an abrupt drop in base level, probably within just the last few thousand years. The trick is figuring out what dropped the base level. Downstream, the gulley begins to look very artificial, then takes a 90-degree turn to peter out to nothing above a catchment. I’m tempted to go back just to examine and understand the drainage.

Obsidian takes us through the deep mud puddle at Arroyo Chavez again. This time there is a moment of tension as one of the wheels starts to spin, but the others catch and we’re through. I really don’t recommend this route to readers.

Then we’re through, and from there head for home.

Pingback: Wanderlusting Mount Taylor, Day 4 | Wanderlusting the Jemez