Wanderlusting the Ortega Formation

Wanderlusting the Ortega Formation was not my original intent, or at least, not my sole intent. I was planning on taking another crack at Arroyo Hondo, the location Gary and I never got to a couple of weeks back. This time I was confident I had my directions straight. Alas, Gary is out of state engaged in a literal labor of love (helping repair a sister’s deteriorating house) and winter is continuing to move in, so I felt I could not wait for him to join me. Anyway, I figured I should know my way around Arroyo Hondo before taking Gary there again.

It turns out this is probably just as well.

But first, as I mentioned in the last post, winter weather was imminent. It did indeed arrive over the next three days:

That’s looking through the screen door into my back yard. We got a good five inches, I’d estimate. Temperatures were in the mid-20s at night and barely got above freezing for about three days. Then the weather warmed up and we haven’t had a real freeze since. Almost all the snow is melted now. But another big storm is forecast for Sunday and Monday, and rain is starting to come down even as I write.

So I was up Friday at a reasonable hour and off to see some rocks. My plan was to visit the principle reference locality of the Ortega Formation to get a picture for Wikipedia. I’d then cut across the Taos Plateau through Carson and maybe get some pictures of Cerro Azul on the way. Then to Arroyo Hondo and hiking up the canyon to the staurolite beds.

The first part of the trip was familiar country. My first photo is a particularly nice view of Valleto Peak.

This is the type section for the Vallito Member of the Chamita Formation. Yeah, spelling. It’s Vallito in all the geologic reports, but Valleto on the BLM topographic map.

For new readers (Welcome!): Almost all images at this site can be clicked for a higher-resolution version. Blue links generally take you to Google Maps to show you where I was when I took the photograph. My camera records GPS coordinates with each shot, assuming it’s got a good lock on the satellite constellation; this particular shot recorded coordinates but they were off enough that I took the coordinates of the peak itself from Google Maps.

Also for newer readers: The Chamita Formation is part of the Santa Fe Group, which includes all the formations that are rift fill of the Rio Grande rift. The Rio Grande rift is a great crack in the Earth’s crust reaching from central Colorado to El Paso, where it becomes lost in the general stretching and fracturing of the crust in the Basin and Range Province. The rift is where the Colorado Plateau has pulled away from the interior of North America. The valley of the Rio Grande River mostly coincides with the rift.

Rifting began around 20 to 30 million years ago and really got going around 15 million years ago. But instead of there being a yawning chasm three miles deep in the Espanola valley, sediments from the higher ground on either flank have filled in the rift. These sediments are now beginning to be eroded out as the entire region is uplifted by hot mantle rock rising from deep below.

The Chamita Formation seems to mark the transition from deposition in a closed basin to deposition along an ancestral Rio Grande that continued south to the Albuquerque area. The Vallito Member is a part of the formation that appears to be floodplain deposits of this ancestral Rio Grande.

I continue on past Ojo Caliente and towards La Madera. Along the way is a very impressive travertine deposit.

For panoramas like this one, you really want to click for the full resolution. It’s almost like being there.

This deposit is located very close to a major fault. It was produced when fluids rich in carbon dioxide (and therefore highly acidic) rose along the fault through limestone beds, dissolving out part of the limestone. When the fluids reached the surface, the carbon dioxide bubbled out, reducing the acidity. This also reduced the solubility of calcium carbonate so that calcite (one of the mineral forms of calcium carbonate) was deposited at the surface as travertine.

The geologic map gives an age range for this travertine from 100,000 to 180,000 years.

What was the source of the carbon dioxide-rich water? Probably heated rock deep below the surface associated with the Rio Grande rift. Travertine deposits are found all along the flanks of the rift, and not necessarily in close association with obvious volcanic fields.

Further on, there are some nice exposures of amphibolite in the valley walls, and I get some pictures for the book.

This is very old rock, around 1.7 billion years in age. It’s mapped as lower beds of the Vadito Group. These are rocks thought to have been deposited in a back-arc basin that formed when an island arc collided with the southern margin of Laurentia, the ancestral core of North America. The island arc glommed onto the edge of the continent and became the “basement” of the crust of northern New Mexico down to about the latitude of White Rock.

The Vadito aphibolite beds were originally basalt lava flows erupted into the floor of the basin. These were later deeply buried and metamorphosed to amphibolite.

I’d like to get a closer look, but the entire canyon wall here is posted private land.

And then I arrive at the Ortega Quartzite type location.

The view is from the road, where the GPS on my camera is finally recording fairly accurate coordinates. I’d like to get closer, but the most obvious route is again posted private land.

Further north I seem to be past the private land, and I set out on foot. I find myself on a quartzite ridge.

This is a pretty good exposure, except for the crusting lichens. Don’t worry; this is just our first close look for the day. We’re going to see lots more.

The Ortega Quartzite was deposited in a later stage of the same basin (the Pilar basin) in which the Vadito Group was deposited. It represents an invasion of the basin by the sea, which deposited an immense thickness of almost pure quartz sand. This was also deeply buried, and recrystallized as quartzite. Quartzite is almost pure quartz and it’s a very tough, resistant rock.

This rock shows what may be relict sedimentary beds.

I’m not geologist enough to be sure these beds didn’t form later, during metamorphosis. I’m also not geologist enough to infer anything about the depositional environment from these beds, such as paleocurrent directions (which way the seawater flowed as it deposited the sand) or even which way was up. (A lot of the rock beds this old are overturned by later tectonic deformation.) In any case, the boulder has come loose from wherever it was originally formed, so its orientation has been randomized.

Well, I’m a little closer to the type location.

Not really better than what I got from the highway. This is already good enough for Wikipedia, so I’m not inclined to take any risks or spend much time getting closer, and the ground is dropping very steeply below me into the river valley below. Which may be private land.

I start back. And, ohhh, I finally score the picture I’m looking for:

That’s almost too gorgeous to give away, but it will be perfect for the Wikiipedia article.

Along the way, I find a large chunk of really beautifully crystallized amphibolite. I decide it will make a nice yard rock.

The large black crystals are an amphibole mineral, likely hornblende. This is a moderately silica-poor mineral that also contains aluminum, calcium, sodium, iron, and magnesium (the composition is quite variable) as well as essential water. “Essential” means that the water is incorporated as a fundamental part of the crystal structure of the mineral. Hornblende is not at all rare, but big crystals like this are just a bit unusual.

I head back south, and the lighting makes this just too good to miss.

La Madera Mountains. That’s also all Ortega Formation quartzite.

I head for Carson. To the north of the town are Tres Orejas (“Three Ears”):

These are volcanic cones of the Taos volcanic field, around 4 million years old.

The town itself:

I wish Gary was along. This was where his great-grandfather (I think) settled and tried to grow soybeans. Together with other settlers, they build a big impoundment for runoff water from the nearby hills and mountains. The impoundment duly filled with water … and the settlers sadly watched as a big whirlpool developed in the middle of the artificial lake and the water all drained into a hidden lava tube beneath. Apparently the Army Corps of Engineers, who seem to be always looking for things to do, tried to seal up the leaks, but there was more than one and the soybean effort failed. Gary will no doubt send me corrections and more details when he sees this post, and I’ll incorporate them.

There’s still a town with a post office, so somebody is eking out a living nearby, but the population seems to be tiny.

A road leads south from here that eventually fetches up near Cerro Azul. This is a kipuka, an island of older rock completely surrounded by younger basalt lava flows of the Taos volcanic field. It’s ancient rock of the Vadito Group, and its location seemingly squarely in the middle of the Rio Grande rift makes it of interest. Unfortunately, the thick flows around it have buried most of the clues to its origin.

Rio Grande gorge:

I was here with Gary not long ago, after a wonderful kayaking trip, but the lighting was not nearly as good. You can see the great thickness of Servilleta Basalt capping the rim of the gorge. Last time I was here, I assumed the layers further down had slumped from the rim, forming what geologists call Toreva blocks; we have quite a few striking Toreva blocks in White Rock Canyon. But looking at these in the better light, I’m not so sure. There is no sign of rotation and it really looks like basalt layers all the way down. Checking the geologic map: It says all the lower stuff is landslide blocks, so I was right the first time. The lack of rotation means these must be relatively shallow slumps rather than Toreva-style deep slumping. Toreva blocks tend to rotate towards the cliff they detach from.

Again, I’ve photographed the area before, but in this lighting this was too good to miss.

Pilar Mesa. A second view:

You can see that the beds in the lower slopes, which belong to the Tertiary Chamita Formation, dip at an angle of about 15 degrees. They’ve been rotated by tectonic activity along the Rio Grande rift. Above is a thin bed of acestral Rio Grande gravel, then Servilleta Basalt, then alluvial fan deposits on top of the basalt. The upper beds are level, showing that there has not been much tectonic motion in the last 5 million years or so.

This time I find the right forest road to Arroyo Hondo without difficulty. The road isn’t great and I worry about whether I’ll find a safe place to turn around. Fortunately, there is an ideal pullout just before the road gets really bad.

A mandible.

There are no Philistines reported up canyon and I am not Sampson, so I leave it.

These are deeper potholes than I’d care to take my car across. You could certainly do it in in a jeep. Further up, the road gets a little hairy even for a jeep in a few places.

Anyway, it looks to be a pleasant hike. I saddle up and move out.

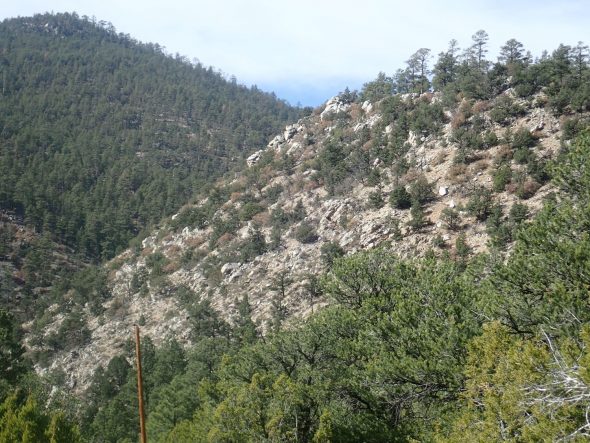

The canyon narrows and the walls are striking exposures of Ortega Formation.

And here.

A couple more.

Here’s a close up of the quartzite on a fresh surface.

The black streaks contain small quantities of magnetite. And I do mean small: I was curious enough once to crush some rock from such a streak, and found that even in quite dark rock, the black magnetite was less than 10% of the volume of the rock. There’s also some sillimanite, aluminum silicate, forming needle-like crystals here and there. Otherwise, this is almost pure quartz.

Some snow from the last storm remains.

Here the quartize seems just a bit less clean.

The geologic map is a bit cryptic, but it does show this as a different informal member of the Ortega Formation.

And then:

I was sure the rock beds I was hiking to are on National Forest land. But here’s a gate and the painted letters insist this is the La Serna Grant, private property, no trespassing, permit required, trespassers will be prosecuted …

Snow.

All I can figure is that the road cuts across a corner of private land that I missed when perusing the jurisdiction map, and the landowner has decided to close the road. I confess this irritates me a little. I’m fine with signs saying you’re crossing private land, please to stay on the road until you reach public land on the other side. I’m fine with closing a road that ends on private land. I feel differently when someone blocks the public’s access to interesting public lands by closing a road.

The fence is trivially easy to cross. I’m sorely tempted. The point of this hike was to get to the Rinconada Formation staurolite beds, and take photos of the Riconada, Pilar, and Piedre Lumbre formations close to their type locality. Lots of interesting geology up there. It’s a wrench. But I turn back.

Another view of the Ortega Quartzite on the way out.

And as I step on a rocky outcrop, there is a sharp pain in my foot. Dang, these boots must be getting old. The pain only gets worse. I look at the sole of the boot; it does not appear to be penetrated by a rock shard. I must have got a pebble in my boot. I take it off; no pebble falls out. I rub the sole of my foot: Owww. I pull my sock off, fearing the worst. Lo and behold, there is a large cactus spine sticking straight out of the sole of my foot. I extract it and my foot is fine.

I have no idea how it got there.

On the drive home, I decide to try to make up for a disappointing hike by examining a channel deposit I’ve noticed before.

The dark, coarse sediment bed in the midst of the fine sediments is really quite striking. I get a closer look. The clasts (rock fragments) in the bed are all Pilar phyllite, a Precambrian rock found in the mountains to the east.

This is very definitely a channel scoured in the beds below. A debris flow out of the mountains, from a thousand-year flood? Possibly. Filling an old channel.

Just up the road, the surface into which the channel was scoured and filled is clearly discernible.

The grassy ledge is at precisely the level of the dark channel fill, and must be an old buried erosional surface — a hiatus in deposition of the Chamita Formation beds here.

When I get home, I check the land jurisdiction map for Arroyo Hondo. The entire canyon is mapped as public land except for the first few hundred feet — which were not posted and had an open access road. The gate seems to be on the boundary between BLM land to the west and National Forest land to the east.

I suspect land grant activism. Under the Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War and transferred sovereignty of this area to the United States, the U.S. pledged to respect existing land grants. The problem is that U.S. land law and Mexican land law did not entirely agree in how they defined property boundaries and property rights, and this created some misunderstanding — some of it likely deliberate — in where grant boundaries actually lay. There are activists in the state who are still disputing some of the awards of good title that were made by U.S. courts over a century and a half ago. And I suspect one of them vandalized a Forest Service gate here.

I prefer to stay away from such disputes. Not my circus, not my monkeys.

Pingback: Wanderlusting Colorado, Day 1 | Wanderlusting the Jemez

Hello. I really enjoyed reading your article this morning – I just randomly happened upon your site while browsing this am looking for potential malachite sites in NM. My wife and I live in the Old Pink Schoolhouse in Tres Piedras and love to hike & hang out in many of the places you mention here. I love the mix of your narratives with geology. We love rocks. We are not as smart about them as you guys, but we love them just the same. So many laundry loads end up with a clinking rock or two left in one of our pockets from rock gathering. Lol. If you are ever in Tres Piedras area, please feel free to stop by and say hello. Cheers! – John & Nicole